God is the best explanation on why there is something rather than nothing

Introduction

G. W. Leibniz the codiscoverer of calculus and a formidable intellectual of his time in the eighteenth-century Europe, wrote: “The first question which should rightly be asked is: Why is there something rather than nothing?” (Aka why does anything at all exist in the first place?) Leibniz came to the conclusion that the answer is to be found in God and not the created substance of the world. God exists necessarily and is the explanation why anything else exists.

Leibniz’s Argument

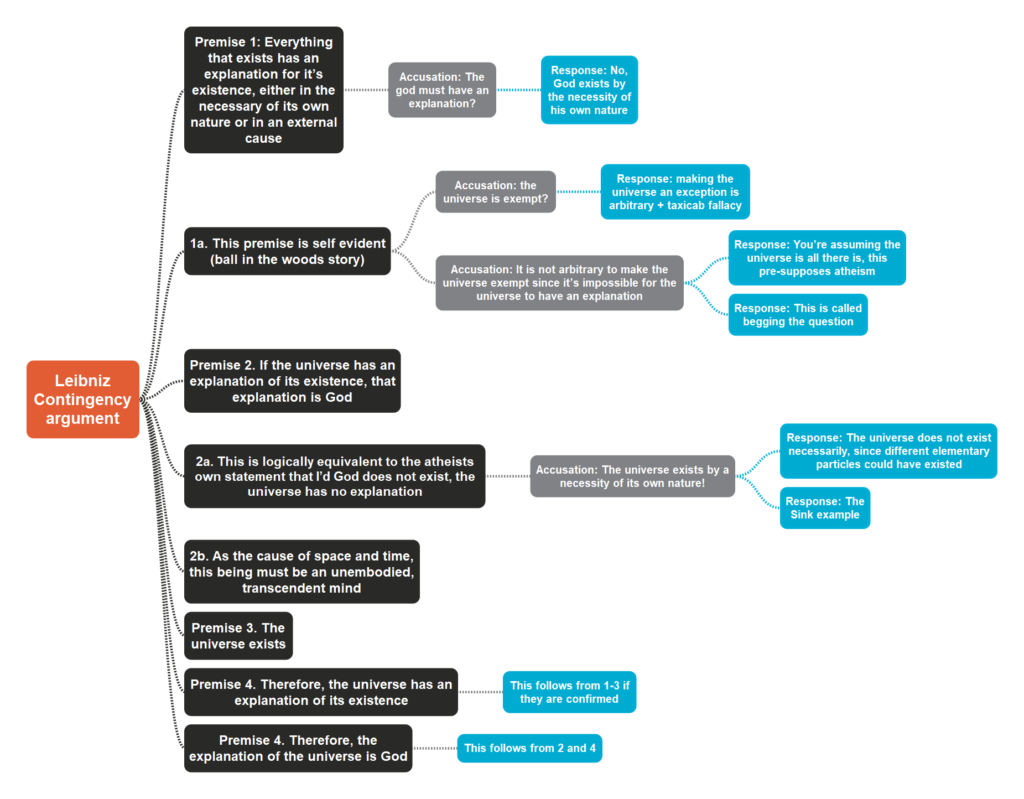

So what is the argument? Here is the basic syllogism which we will get into here.

There are three steps/premises in Leibniz’s reasoning:

1. Everything that exists has an explanation of its existence.

2. If the universe has an explanation of its existence, that explanation is God.

3. The universe exists.

So What would follow logically from these three premises? 1 to 3 — If everything that exists has an explanation of its existence and the universe exists, then it would follow logically that:

4. The universe has an explanation of its existence.

Now notice that premise 2 says that if the universe has an explanation of its existence, that explanation is God. And 4 says the universe does have an explanation of its existence. So from 2 and 4 the conclusion logically follows:

5. Therefore, the explanation of the universe’s existence is God.

So in full

1. Everything that exists has an explanation of its existence.

2. If the universe has an explanation of its existence, that explanation is God.

3. The universe exists.

4. The universe has an explanation of its existence.

5. Therefore, the explanation of the universe’s existence is God.

This is logically airtight for an argument because if the first three premises are true, then the conclusion cannot be avoided. It would not matter if the sceptic doesn’t like the conclusion. It doesn’t matter if they have other objections to God’s existence. If they grant the premises, they grant the conclusion, they have no choice.

Premise 3 is undeniable for anyone seeking truth, the universe clearly exists! So the atheist would likely deny steps 1 or two if they want to remain rational and be an atheist at least.

So what are the objections and answers to premise’ 1 and two?

Premise 1: Everything that exists has an explanation of its existence.

Objection: God Must Have an Explanation of His Existence

At first premise 1 might seem to have a fatal flaw in that if everything that exists has an explanation of its existence, and God exists, then God must have an explanation of His existence surely? But when you explore this it is a bizarre statement because the explanation of God’s existence would be some other being greater than God and that’s impossible (God is the greatest maximal being. Whatever was considered greater than God would be God and what was lesser is not God. Since it’s impossible to be greater than God, the first premise is false. Some things must be able to exist without any explanation (The Bible claims to have an uncreated God).

The believer will say God exists inexplicably. The sceptic will say, “Why not stop with the universe? The universe just exists inexplicably.” So have we reached a stalemate?

Answer to the Objection: Some Things Exist Necessarily

This objection to premise 1 is based on a misunderstanding of what Leibniz meant by an “explanation” and we will now give a fuller explanation of premise 1. In Leibniz’s view there are two kinds of things:

1. Things that exist necessarily

2. Things that are produced by some external cause.

Let me explain.

(a) Things that exist necessarily exist by a necessity of their own nature. It’s impossible for them not to exist. A quantity of mathematicians believe that numbers, sets, and other mathematical entities exist in this form. Nothing caused them to exist, they simply exist by the necessity of their own nature.

(b) By contrast, things that are caused to exist by something else don’t exist necessarily. They exist because something else has created them. Physical objects we know like people, planets, and galaxies belong in this type of category. So we can understand that when Leibniz says that everything that exists has an explanation of its existence, the explanation may be found either in the necessity of a thing’s nature or else in some external cause. So premise 1 could be more clearly stated in the following way:

1. Everything that exists has an explanation of its existence, either in the necessity of its own nature or in an external cause.

So now the objection clearly does not meet the affirmed premise. The explanation of God’s existence lies in the necessity of His own nature. As even the sceptic recognises, it’s impossible for God to have a cause. So Leibniz’s argument is really an argument for God as a necessary, uncaused being with the question of anything’s existence in mind. So what we find is this objection actually helps clarify and indeed exalt who God is. If God exists, He is a necessarily existing, uncaused being.

Defense of Premise 1: Size Doesn’t Matter

So another reason for thinking the first premise is true comes from a well known illustration Professor William Lane Craig draws upon often for this argument to prove the self-evidence for the premise.

“Imagine that you’re hiking through the woods and you come across a translucent ball lying on the forest floor. You would naturally wonder how it came to be there. If one of your hiking partners said to you, “Hey, it just exists inexplicably. Don’t worry about it!” you’d either think that he was crazy or figure that he just wanted you to keep moving. No one would take seriously the suggestion that the ball existed there with literally no explanation. Now if you increase the size of the ball in this story so that it’s the size of a car. That wouldn’t do anything to satisfy or remove the demand for an explanation. Suppose it were the size of a house. Same problem. Suppose it were the size of a continent or a planet. Same problem. Suppose it were the size of the entire universe. Same problem. Merely increasing the size of the ball does nothing to affect the need of an explanation”.

On Guard, William Lane Craig

The Taxicab Fallacy

There would be possible times when sceptics will say that premise 1 is true of everything in the universe but is not true of the universe itself. Everything in the universe has an explanation, but the universe itself has no explanation. But this response commits what has been called the “taxicab fallacy” (you’ll see why this is a great name in a second). As the nineteenth-century atheist philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer made clear that premise 1 can’t be dismissed like a hack once you’ve arrived at your desired destination! You can’t say everything has an explanation of its existence and then suddenly exempt the universe. That would be an utterly inconsistent position for the sceptic.

It would be arbitrary for the sceptic to claim that the universe is the exception to the rule. (This argument does not make God an exception to premise 1 as stated earlier with the expanded premise) The illustration of the ball in the woods expresses that increasing the size of the object to be explained, even until it becomes the universe itself, does nothing to remove the need for some explanation of its existence.

Science is also not on the side of the sceptic. The field of Modern cosmology is devoted to the search for an explanation of the universe’s existence. This outlook would damage science itself.

Accusation: It Is Impossible for the Universe to Have an Explanation

How about this scenario: it’s impossible for the universe to have an explanation of its existence. Why? Because the explanation of the universe would have to be some prior state of affairs in which the universe didn’t yet exist. But that would be nothingness, and nothingness can’t be the explanation of anything. So the universe must just exist inexplicably. Checkmate theists.

Well this would be a poor response and clearly problematic. It would take by assumption that the universe is all there is, so that if there were no universe there would be nothing. So what this objection is basically doing is presupposing is that atheism is true! The atheist is doing what philosophers call begging the question (The fallacy of begging the question occurs when an argument’s premises assume the truth of the conclusion, instead of supporting it). Leibniz would agree that the explanation of the universe must be a prior state of affairs in which the universe did not exist. But that state of affairs is God and His will, not nothingness. So by all appearances premise 1 is more plausibly true than false, which is all we need for such a standard to be reasonable.

Premise 2: If the universe has an explanation of its existence, that explanation is God.

Sceptics will agree with Premise 2

What, then, about premise 2, that if the universe has an explanation of its existence, that explanation is God? Is this more plausibly true than false?

What’s really difficult for the sceptic at this point is that premise 2 is logically equivalent to the typical atheist response to Leibniz’s argument. Two statements are logically equivalent if it’s impossible for one to be true and the other one false. They will stand or fall together.

So what does the atheist almost always say in response to Leibniz’s argument? As we’ve just seen, the atheist typically asserts the following:

A. If atheism is true, the universe has no explanation of its existence. This is precisely what the atheist says in response to premise 1.

The universe just exists inexplicably. But this is logically equivalent to saying:

B. If the universe has an explanation of its existence, then atheism is not true.

So you can’t affirm (A) and deny (B). But (B) is virtually synonymous with premise 2! (Just compare them.) So by saying in response to premise 1 that, given atheism, the universe has no explanation, the atheist is implicitly admitting premise 2, that if the universe does have an explanation, then God exists.

Another Argument for Premise 2: The Cause of the Universe: Abstract Object or Unembodied Mind?

The universe is all of space-time reality, including all matter and energy. It follows that if the universe has a cause of its existence, that cause must be a nonphysical, immaterial being beyond space and time. What is clear is there are only two sorts of things that fit this description: an abstract object or unembodied mind. The difficulty with position an abstract object is they don’t have the [ower to cause anything, that is part of what it means to be abstract. For example, 39 can’t cause anything, some people doing creative accounting during the financial crisis tried this very thing and that didn’t work out very well at all! As C.S. Lewis has famously in said in similar words “First give me the one pound and another and I’ll give you the two”. So the cause of the existence of the universe must be a transcendent Mind, which is what believers understand God to be.

If this argument is successful, it proves the existence of a necessary, uncaused, timeless, spaceless, immaterial, personal Creator of the universe. This is no sky fairy, for someone with the traditional properties of God and that aligns perfectly with Christian belief.

Atheist Alternative: The Universe Exists Necessarily!

What does an atheist do at this junction then? Well there is a wild option still on the table which regards premise 1 and say instead that, “yes, the universe does have an explanation of its existence. But that explanation is: The universe exists by a necessity of its own nature”. For the atheist, the universe could serve as a sort of God-substitute that exists necessarily. This is a very bold step and William Lane Craig states he does not know of any scholar who holds to this view.

There are good reasons atheists and sceptics alike do not want to embrace this as an option. Nothing in the universe, galaxies, dust, radiation etc. Seem to exist necessarily. When the universe was very dense in the past, none of them did exist!

Ok drill deeper you could say, what about the matter that these things are made of? Maybe the matter exists necessarily, and all these things are just different configurations of matter? The issue with this is that, according to the standard model of subatomic physics, matter itself is composed of tiny fundamental particles that cannot be further broken down. The universe is just the collection of all these particles arranged in different ways.

But couldn’t a different collection of fundamental particles have come into existence instead of the current ones? Does each and every one of these particles exist necessarily? Notice what the atheist can’t say at this point. He cannot say that the elementary particles are just configurations of matter which that could have been different, but that the matter of which the particles are composed exists necessarily. He can’t say this, because elementary particles aren’t composed of anything! They just are the basic units of matter. So if a particular particle doesn’t exist, the matter doesn’t exist. Now it seems obvious that a different collection of fundamental particles could have existed instead of the collection that does exist. But if that were the case, then a different universe would have existed.

Using an illustration to provide clarity, look at your kitchen sink, could your sink be made of ice? This isn’t to ask if you have an “ice sink” in the place of your metal kitchen sink (I’m assuming that!). But it is to ask, if your very sink made of metal could be made of ice. The answer is clearly no, it would be a different sink, not the same sink. Broadening the size, a universe made up of different particles, even if they were identically arranged like in this universe, would be a different universe.

The natural next step here is that the universe does not exist by a necessity of its own nature.

Objection: My body exchanges all its material for new ones?

Scientists tell us that every seven years the matter that makes up our bodies is virtually completely recycled. Despite all of this, our bodies are identical to the body we had prior, we appear for all circumstances, the same person. Could the same be said of the universe? A different set of materials to form something identical looking?

The problem with this is that the difference between possible universes is no kind of change at all, for there is no enduring subject that undergoes intrinsic change from one state to another.

So the comparison of a human body to the universe made up of particles is not on part stage-wise to each other, the universe would be like 2 bodies with no connection at all. There is no one who thinks that every particle in the universe exists by a necessity of its own nature (That I know of!). So from this we can state that neither does the universe composed of such particles exist by a necessity of its own nature.

This would be the case regardless whether we think of the universe as itself an object (how one tree is not the same as another), or as a collection or group (2 herds of sheep varying), or even as nothing at all over and above the particles themselves.

The claim that the universe does not exist necessarily becomes clear when we come to the understanding that a completly different set of building blocks at the foundation of the universe could have quite different elementary particles we know. This type of universe would be built so differently it’s laws of nature would vary. Even if we took our laws of nature we live by as logically necessary, still it’s possible that different laws of nature could have held because substances embedded with different properties and capacities than our fundamental particles could have existed.

It is quite clear that it would be a different universe altogether. So sceptics have not been so bold as to deny premise 2 and say that the universe exists necessarily. Like premise 1, premise 2 also seems to be plausibly true.

Conclusion

Given the truth and reliability of the three premises, the conclusion is the only one left on the table, that God is the explanation of the existence of the universe.

As well as this, the argument posits that God is an uncaused, unembodied Mind who transcends the physical universe and even space and time themselves and who exists necessarily. There are many other forms of contingency argument that have been formed by philosophers in more recent years, some are more complex, others are as simple as this one, but this isn’t a bad introductory argument for the Christian who wants to ground the God is the force behind why there is anything at all in th first place.

Cheers Leibniz!

Mindmap

Sources

- 1. G. W. F. von Leibniz, “The Principles of Nature and of Grace, Based on Reason,” in Leibniz Selections,

- P. Wiener (New York: Scribner’s, 1951), 527.

Resources

Here are a list of resources to aid you on your quest to grapple with the simple (but also complex) argument. Many of these are listed at my website 1c15.co.uk.

Videos

Animated video: Leibniz Contingency Argument Animated Video

Advanced discussion: The Argument from Contingency – Josh Rasmussen Ph.D. & Lance Hannestad

Debate: Argument from Contingency. Alex O Connor vs Cameron Bertuzzi

Debate: Is the Contingency Argument Persuasive? Dr. Josh Rasmussen vs Scott Clifton

Lecture: Why does anything at all exist? | William Lane Craig

Lecture: The Leibnizian Contingency argument | Tim Stratton

Podcasts

Exploring the Contingency Argument with Dr. Josh Rasmussen

Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

YouTube Channels:

Books

On Guard: Defending Your Faith with Reason and PrecisionReasonable Faith

Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology

Necessary Existence

0 Comments