The living wager: You should believe in Christianity if there is a fair chance it’s true

This is a strengthened version of Pascal’s wager which typically has said that “even if there is the smallest chance Christianity is true, you should believe it”. This wager places the value that if Christianity is at least 50% true, you should follow it. The wager can be summed up in this sentence:

It is rational to seek a relationship with God and live a deeply Christian life, because there is very much to gain and relatively little to lose

We have updated information from the time of Pascal to defend his wager more sufficiently. Michael Rota who wrote the new book “Taking Pascals Wager” lays out a premise argument like so:

- If Christianity has at least a 50% chance of being true, then it is rational to commit to living a Christian life

- Christianity does have at least a 50% chance of being true

- It is rational to commit to living a deeply christian life

In order to appreciate this Wager, we need to explore decision theory

Decision theory

This is basically about how to make good decisions in circumstances of risk or uncertainty. This can be applied to mundane tasks such as taking a taxi vs taking a bus or significant events like career choices. There are three foundational concepts: states, strategies and outcomes

States — A possible way things might be

Strategy — A possible action the decider might take

Outcome — The resulting situation when taking a strategy and a certain state is actual

Decision theory offers 2 principles to guide you when taking risks

- Try to maximise your expected value

- Pick a strongly dominant strategy if possible. If not, pick a weakly dominant strategy

What does it all mean?

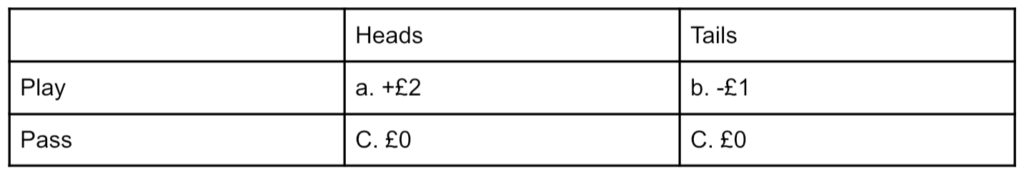

- Say I offer you a bet. We ask a trusted friend to flip a fair coin but not tell us whether it came up heads or tails. Then I ask you to decide whether to play or pass

- If you choose to play it will cost you £1.

- If the coin came up heads, you will get your £1 back and I will give you £2 of my own. So you’d gain a £3 total

- If you choose to play and the coin comes up tails, I’ll keep your £1

- If you choose to pass, no money will be changed either way

Would you take the bet? Decision theory says you should because of the first principle (maximise your expected value).

So let’s workout the probability using this table.

A coin: ½

(£2 x ½ ) + ( -£1 x ½) = 0.5 (Strategy play)

So if you played this bet a number of times every time you would win on average 50p.

Now compare that to passing

(£0 x ½ ) + ( £0 x ½) = 0 (Strategy play)

Since playing has a greater value than passing, you should play, every time.

We don’t usually have precise-like probabilities like this to assign to states. But we have scenarios like “I should do this because it might help or there’s no harm in doing it anyway” or “I’ll do that because there’s nothing to loose and everything to gain”. This is called a weakly dominant theory.

Say you borrow a bicycle of your friend and you drive to the store to buy some snacks. As you begin to lockup your bike you think “this part of towns pretty nice, no one is likely to steal my bike and I will be able to see it from the shop window”. Should you lockup the bike? It’s clear enough you should lockup the bike. Here’s why.

If a thief strolls past, locking is obviously far better. If a thief doesn’t pass buy, locking is no worse than not locking. So locking is a weakly dominant strategy.

Weakly dominant strategy — yields a better or at least equally good outcome

In decision theory, always pick this unless there is a strong dominant strategy.

Strongly dominant strategy — yields a better outcome in every possible state

So Decision theory is how to make good decisions in circumstances of risk or uncertainty. 3 foundational concepts, 2 guiding principles.

Pascal’s wager

Either God exists or not, those are 2 possible states of the world — you need to make a decision. Will you live your life as if God exists? Or not?

So Let’s look at the comparison

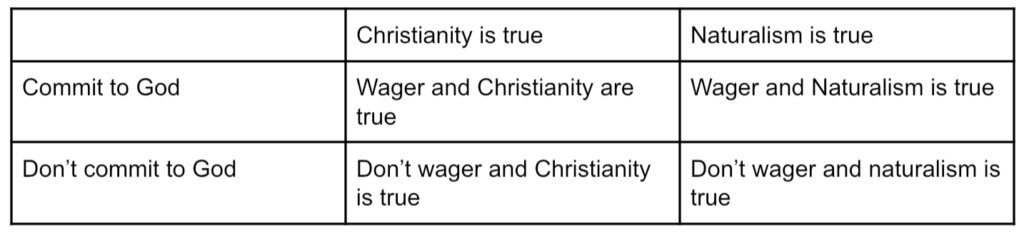

States: Christianity is true or naturalism is true (God exists/God doesn’t exist).

Strategies: commit to God or don’t commit to God. This isn’t saying force yourself to believe in God, but you can choose to seek and pursue a relationship with God. This is available to the believer and the inquiring agnostic.

Both will engage in prayer, the intention to live morally in accord with what God wants, attend religious services, form friendships with religious believers, read and study sacred writings and discuss religious questions. No hypocrisy or dishonesty should be involved for the agnostic, their prayers can be conditional “if you’re there God, help me with X and thankyou for Y”. This individual must have a sincere openness to the possibility of God and a desire to search for him and a willingness to accept belief in God should it come.

This type of commitment is not necessarily equivalent to faith because it does not necessarily include belief but it may very well be an important stepping stone towards faith. Not committing to God could take many forms, so here we’ll define it as the absence of commitment.

So you’re either seeking God or not. Here’s our decision matrix

Strategy

Wager and Christianity is true

Goods:

- Maximised your chance at eternal life

- Bring joy to god and all others who are with him in heaven (God presents himself as a father who seeks his children)

- Exhibited virtue of expressing gratitude to God

- More likely to benefit from divine aid for moral; and spiritual growth

- More likely to be aware of God’s love

- More likely to help others in their journey to God

These are all points that could be expanded.

Wager and naturalism is true

If this view is true, yet you committed to God, have you wasted your life? According to psychological and sociological data no.

There are 3 goods you would benefit from if naturalism is true but you made a commitment to Christianity

Goods

- Increased chance of greater life and satisfaction and happiness

- Increased chance of longer life

- Increased chance of exercising certain civic virtues

What evidence do we have for these three?

Increased chance of greater life and satisfaction and happiness

The Handbook of Religion and Health, 2nd editionreport shows:

- Religious participation can indirectly affect wellbeing through directly affecting other areas of life

- Religious people are less likely to divorce and more likely to have stable families. They systematically went through 79 studies and these studies cover people with marriages as much as 28 years (so not 1 year marriages)

- Religious people have more social contacts and greater satisfaction with their social support. 82% of 74 quantitative peer reviewed studies showed an positive relationship between religiousness and social support

- Religious people have a higher self-esteem. 61% of 69 peer reviewed studies. Only 3% of studies showed they had lower self-esteem

- Religious people have more optimism. 81% reported significantly positive relationships between religiousness and optimism

- Religious people are more hopeful. 73% of the studies showed a positive relationship between religiousness and hopefulness while the rest showed no correlation

- Religious people have a greater sense of meaning and purpose in life. 93% (42/45 studies) showed a positive relationship

Chaeryoon Lim and Robert D Putnam in a study (Religion, Social Networks and Life Satisfaction) tell us “when compared with other correlates of well-being, religion is just as or more potent than education, marital status, social activity, age, gender, and race. Other studies find that religious involvement has an effect comparable to or stronger than income.”

There’s a lot more that can be said… buy Michael Rota’s Taking Pascal’s Wager. But the jist is even if naturalism is true but you hold to God, it benefits you even if Christianity wasn’t true in the end.

Increased chance of longer life

Michael E Mcullough and others in a study Religious Involvement and Mortality: A Meta-analytic Review analysed 42 studies on the connection between religious involvement and mortality, after controlling for other variables, individuals involved in religion had a substantially higher chance of still being alive at the end of the studies.

Increased chance of exercising certain civic virtues.

In a work by Robert D. Putnam (Harvard) and David E. Campbell (Norte Dame) called American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us, the data shows religious Americans tend to volunteer more, give more to charitable causes (both religious and secular), greater degrees of civic involvement.

They go on to say specifically “the statistic suggest that even an atheist who happened to become involved in the social life of a congregation (perhaps through a spouse) is much more likely to volunteer in a soup kitchen than the most fervent believer who prays alone. It is religious belonging that matters for the neighbourless, not religious believing”.

Costs of this wager:

- Lost time spent in prayer, church etc.

- Loss of sense of control over your life

- Disruption in your relationships

- Give up certain pleasures outside certain contexts

So in a nutshell if you believed in God but naturalism was true

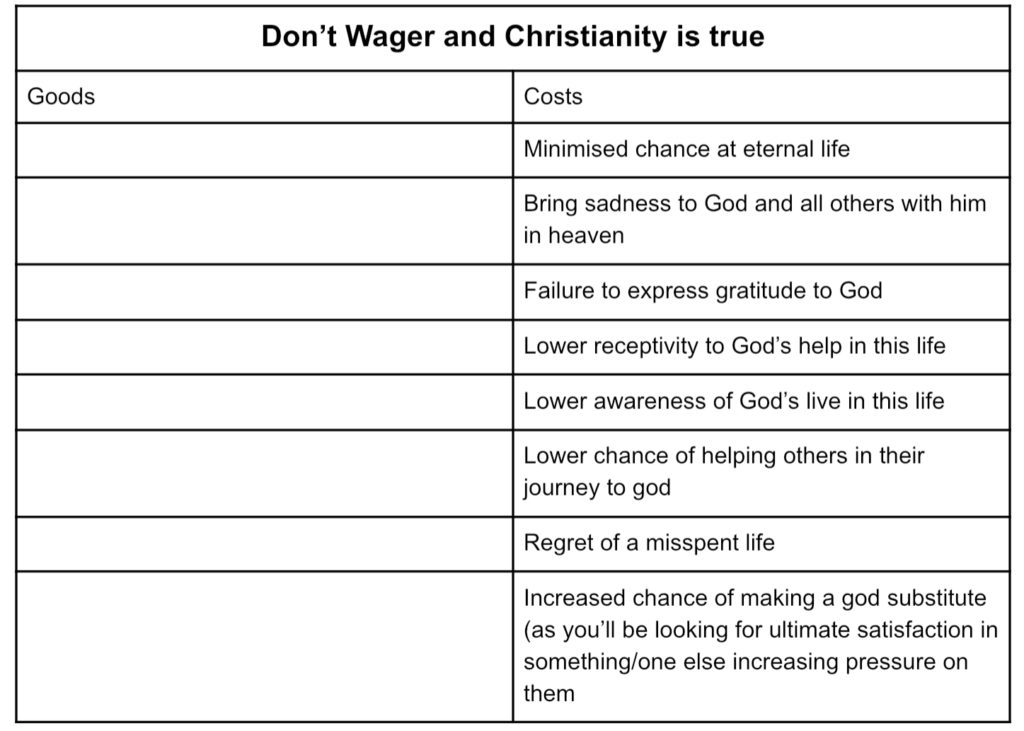

Don’t Wager and Christianity is true

Costs

- Minimised chance at eternal life

- Bring sadness to God and all others with him in heaven

- Failure to express gratitude to God

- Lower receptivity to God’s help in this life

- Lower awareness of God’s live in this life

- Lower chance of helping others in their journey to god

- Regret of a misspent life

- Increased chance of making a god substitute (as you’ll be looking for ultimate satisfaction in something/one else increasing pressure on them

Don’t Wager and Naturalism is true

Goods

- Extra time for other activities

- Greater sense of being in control of your life

- Reduced disruption in your relationships

- Retain certain pleasures

Costs

- Increased chance of lower life satisfaction

- Increased chance of shorter life

- Decreased chance of exercising certain civic values

Results

Assessing the outcomes

Christianity + Wager clearly beats No wager + Christianity

What about the other two? Wager and naturalism being true has goods and costs, as does no wager and naturalism being true.

Wager & Christianity has the best outcomes but even if it were close, you should still choose Christianity because of the benefits. So the small gains and costs of the other views aren’t worth it.

Symbolically, it could be represented like this:

- Christianity + Wager = £1,000,000

- No Wager + Christianity = £0

- Wager + Naturalism = £25

- No Wager + Naturalism = £0

These values arn't exact, all it's trying to say is the differences when you weight them appear vast for God over no God

Would you want to risk losing £1,000,000 if these were your choices? This is all before we evaluate the evidence for God which helps with your decision making. So starting with the wager, we can determine that Christianity is worth the risk and is the best option on the table. And you should explore it. Or at a minimum, God is worth exploring.

So this scenario God weakly dominates in this table. I would argue with the arguments and evidences for God and evidence for Christianity’s truth it becomes a strongly dominant theory.

If Christianity is true, much is to be gained, if naturalism is true, not much is gained.

Pascals Wager: top objections

Objection 1: You can’t force yourself to believe in God

Well, why would I disagree with that? This objection a straw man. The updated wager asks you to commit, but commitment does not necessarily include belief. By committing to God you’re being asked to do actions that you can do. What might they be? Prayer, we can all do that for example you could say something along these lines “God, if you’re there, please give me faith or at least give me more evidence to make a better informed decision about you”. You can also live a better life in moral accord with what God would want. You can attend religious services, form friendships with religious believers and discuss religious questions and study sacred writings.

These all can be done. Nothing asked of here is too difficult, these are all reasonable to explore—theres no blind faith required.

Objection 2: Pascal’s reasoning leads to absurdities

There’s a thought experiment put forward by Nick Bostrom. The point of it is to show that if we consistently apply the principles underlying Pascal’s wager it would lead us to do things which we know are absurd.

Imagine a man who approaches Pascal in a dark alley and demands that Pascal turn over all of the money in his wallet. Seeing that the mugger doesn’t have a weapon, Pascal says “nah!”. The mugger then tries to convince Pascal to turn over the money in his wallet by essentially making a bet. The mugger promises to bring Pascal 10 times the amount of money that is currently in his wallet by tomorrow. Pascal doubts that promise so the mugger reminds Pascal that it is at least possible that he is telling the truth and he asks Pascal to assign a probability to the likelihood that he is telling the truth. Pascal gives a really low number like 0.0000001%. The mugger then raises the amount of money he promises to return until the expected value essentially swamps the low probability that Pascal gave. Pascal says he sees no problem with the math, so he turns over his wallet. Of courses that is absurd—which is the point of the experiment.

Does this disprove Pascal’s wager? It is successful when it aims at a particular version of Pascal’s wager, the weakest version that internet atheists love to beat up on. The weak version says “as long as there’s any non zero possibility that Christianity is true, then it would be rational to commit to God even if it’s only a 0.0000000% chance. But when this objection is aimed at Michael Rota’s updated version of Pascal’s wager it no longer works as the updated version only works when there’s at least a 50% chance of Christianity being true. Bostrom doesn’t concern this Wager.

Objection 3: The Wager is immoral

First

Pascal’s wager is selfish because you’re motivated out of the desire to get as many eternal goodies as yourself as possible. The response to this would be that you don’t have to be motivated by self-interest to take the wager. It’s not just your own eternal happiness you have to consider. You might consider the wager because you want to bring joy to God to all the others that are in heaven. You might commit to help others in the most important way possible. Or perhaps, you may feel you have a possible moral duty to commit to God.

Say you’re walking past someone’s house and you see over a fence a kid with his face down in the pool, you think, it’s hard to see through the trees. You are afraid this might be a drowning crowd, it’s 50/50 you can’t really tell, what should you do? It’s reasonable to think that you have a moral duty to go and check, it would be wrong of you to ignore it. If there’s a lock on the fence, you may even feel obligated to break that lock to save the drowning child. If you’re wrong then yes there’s a cost there but when you reflect on what is at stake, you felt the obligation. The Wager takes the same situation—if it has a 50% chance of being true, you may feel you have a moral obligation to check it out.

You also might commit if you desire to grow morally, after all, committing to God would maximise your chance of receiving divine assistance for moral or spiritual growth.

Even if you did just take the wager to maximise your chance at eternal life, is there anything wrong with that? Absolutely not! That’s good in itself.

Second

A second version of this wager as immoral would be to say the person who takes the wager really isn’t taking pleasure in God himself, they’re just using God as a means to an end. Any God isn’t fooled or pleased by a Wagerer like that.

Response: The wager doesn’t have to have this attitude. It’s not just seeking some candyland, you certainly couldn’t say that about relationship with God which isn’t just some cosmic goodie. It isn’t clear that God isn’t pleased by a wagerer that at least takes the initial step out of self-interest. For example, the Prodigal Son—it was the sons self-interest to come back, yet the father welcomed him back with open arms. Now its certainly better to love God out of his goodness over fear, but we all have to start somewhere. The wager is aimed at someone who doesn’t believe in God. So that initial commitment, even if base don self-interest, can be an initial step on a journey to real faith and a pure love of God.

Third

A third version might be that by taking the wager you risk deceiving yourself. You may come to believe simply for our psychological reasons, not because of the evidence. And therefore you are risking becoming ensnared in an illusion and its wrong to open yourself up for that possibility.

What objections would they have in mind? Well there’s a study by Jack Brehm Postdecisn changes in the desirability of alternatives. He found that in the act of choosing one consumer product over another caused one to value the chosen product more highly than before and the unchosen product less highly than before. Could this apply to religion? Specifically Christianity here?

Response: I would agree you shouldn’t do this just because you’ve chosen it. But if you think the evidence is roughly balanced or even in favour of that claim, then the situation is very different. The risk of self-deception goes both ways. No matter which way you choose to live your life there will be non-rational factors pulling you, affecting what you believe to be true.

Taking a course of action that may result in illusion should not be ruled out automatically. Say your brother has been captured and you get sent letters from the terrorists and the only way to communicate via these letters. You arn’t 100% sure they have him but the terrorists allow you letter communication, is it wrong to write letters even if you arn’t sure they have your brother? Well not really, even if it isn’t him, it’s worth the risk, you could after all, be risking your brothers life if you don’t write back.

Objection 4: The cost of commitment is too high

Some may see the commitment to the God of Christianity too high to be wrong, they can’t take a risk. For example, the Father wants to become a Christian, he has a a large family and a wife but is in a country where it could get him killed. Does the wager still apply in this situation?

- Well firstly there are people who face negative but not major consequences (becoming a Christian in the UK for example)

- Then there’s people who face major but not catastrophic consequences (Richard Dawkins becoming a christian perhaps!)

- Then there’s those who the consequences would be catastrophic consequences

This is a case by case evaluation. 1 and 2 arn’t that weighty but the third is where it becomes more of a challenge. 1 and 2 forming new communities would be hard. One potential evaluation is look at deeply religious people in your own predicament, what’s their outcome like? Was it worth it? I have fortunately met people who have lost a lot falling into category 3, but would do it all again even if it was hard because the consequences was worth the risk.

If Christianity has a 50% chance or higher of being true, the Wager is worth it and for category 3, the witness of others can certainly help. Without being in that category, it is hard for me personally to evaluate without bias since I’m category 1. The goods outweigh the goods and costs of the other views.

In view 3 if you commit say 50% chance or less of martyrdom but if you don’t commit to God and he exists eternally, then 50% or more of something worse. Martyrdom & eternity with God vs no martyrdom and eternity separated from God. God is still a better rational outcome.

Objections 5: The wager ignores other gods/religions

Pretend that Islam is the only rival religion for now, particular the strand that say rejecting Islam sends you to hell (the most common version). In this case, our decision matrix would look like so:

These are just general restrictions. If you commit to Christianity, but Islam is true, one looses greatly by being a Christian and the same holds if you substitute any other religion promising eternal misery for Christians. Academic literature points to this “many Gods” objection that eternal misery brings — you want to be right.

Response

First, nothing in this objection challenges the conclusion from the basic argument that it is better to commit to God in a Christian way than to not be religious at all. Committing to god in the Christian way still weakly dominates not committing to any religion at all. Compare outcome 1 to 7; outcome 2 to 8; and outcome 3 to outcome 9. All this objection shows is the basic argument gives you no way to choose between Christianity and another religion.

So is there a way to choose? It’s actually quite simple—examine the evidence. Examine, evaluate and follow the religion most likely to be true. Ask questions like: does the moral content of this religion seem compatible with the claim that its been revealed by God? Or in non-theistic religions, by reason. Are there strong arguments from history? Science? Philosophy? Against this religion? How do those who hold from that religion respond? Are those responses convincing? Is there any positive evidence in favour of this religion from history, science, philosophy, archeology etc. You don’t need to be an expert to do this. If you read the arguments for God’s existence on this site and look more into them and are convinced they give Christianity at least a 50% chance of being true or higher level of confidence in the truth, you should follow Christianity.

So we started with a chance of choosing God over no God. From there it was worth choosing Christianity over other religions and looking at the evidence will help you there. So the wager can be presented in phases.

- If Christianity has at least a 50% chance of being true, then it is rational to commit to living a Christian life

- Christianity does have at least a 50% chance of being true

- It is rational to commit to living a deeply christian life

I think we’ve established the truth of premise 1 looking at the benefits of Christianity over naturalism. Premise 2 can be established by looking at evidences for the existence of a personal God, defending the reliability of the Bible but most importantly, the evidence for the resurrection.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Taking-Pascals-Wager-Evidence-Abundant/dp/0830851364

0 Comments