Are miracles improbable?

So we’ve dealth with impossibility, now let’s lower the bar, what abut improbability? Which may feel after for a sceptic to argue for. If you’ve seen any debates with Bart Ehrman this is his biggest objection to the resurrection he raises. He explains in a debate with William Lane Craig

“What are miracles? Miracles are not impossible, I won’t say they’re impossible. You might think they are impossible… I’m just going to say that miracles are so highly improbable that they are the least possible occurrence in any given instance, they violate the way nature naturally works. They are so highly improbable, their probability is so infinitesimally remote that we call them miracles. No one on the face of this earth can walk on lukewarm water, what are the chances of one of us can do it? Well none of us can, so let’s say the chances are 1 in 10 billion. Well, suppose somebody can, well that’s 1 in 10 billion, but in fact none of us can! What about the resurrection of Jesus? I’m not saying it didn’t happen, but if it did happen it would be a miracle. The resurrection claims are not only did Jesus come back to life, he came back to life never to die again. That’s a violation of what naturally happens….it’d be so highly improbable that we can’t account for by natural means. A theologian may claim that it’s true and we’d have to argue with a theologian on theological grounds because there are no historical routes to argue on. Historians can only establish what probably happened in the past and by definition, the miracle is the least probable occurrence. And so by the very nature of the canons of historical research, we can’t claim historically that a miracle probably happened, by definition it probably didn’t”.

Bart Ehrman in a debate with William Lane Craig

It’s an impressive sounding argument, but there are some areas we can expose. Bart’s biggest problem with the resurrection is

- The resurrection is a miracle

- By definition miracles are the least probable thing that could happen. What is most improbable should be dismissed a priori

- Therefore we must dismiss the resurrection a priori and it cannot be a competing theory

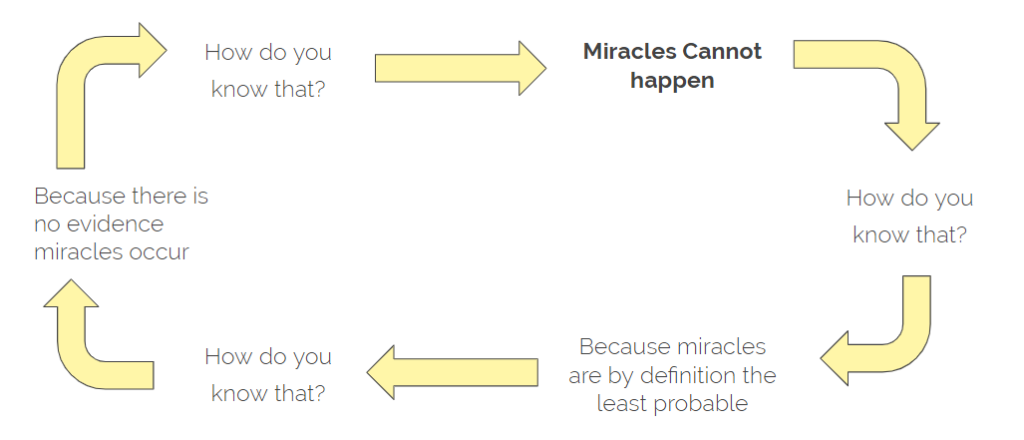

This is similar to Hume’s argument where he states that miracles are impossible. It appears to be basically the same argument, except, Hume states miracles are impossible, Bart says miracles are improbable, therefore, the same logic will apply and the same problems result.

As Hume says, that the uniform testimony of history shows that natural laws cannot be violated and therefore miracles are impossible. Ehrman is simply saying that since billions of people have not been raised from the dead, he’s established it probably cannot happen. Therefore, Jesus’ resurrection is improbable as well. But like Hume, this is just arguing in a circle. So just switch out impossible for improbable and Ehrman’s reasoning follows the same error-filled logic that Hume attempted.

But we should also ask, why must a miracle be the least probable by default in all circumstances? Why do we have to presuppose this and evaluate claims with this to restrict us? And tell us how to think as we evaluate the evidence for something? What is the evidence that favours the theory of resurrection has happened? Why do we have to presuppose naturalism is already probably true, and that a resurrection cannot happen? Is that really being open to the evidence and accepting the most rational conclusion? Or dismissing the resurrection theory because it doesn’t cohere with our already determined worldview? Should we not be open to the evidence instead of trying to make it fit our already determined beliefs?

Ehrman’s argument is the resurrection should be dismissed outright as improbable, regardless of the evidence, because they probably don’t happen. But he can only conclude this if he discounts evidence which favours a resurrection happened. It actually doesn’t address the evidence, it is arguing as if its conclusion, a resurrection did not happen, is already true.

Ehrman only concludes this because resurrections have not happened on a rapid scale, therefore it probably didn’t happen this time. This does nothing to actually evaluate the specific evidence for this specific event, but instead a priori (dismissed out of hand) excludes any theory however likely it is, that disagrees it’s your preconceived notion about how reality should work. Each miracle claim should be judged on a case-by-case basis and we should look at the evidence specific to that claim, not dismiss one possibility because we a priori assume it probably cannot happen. How can you make any progress in anything anywhere if you dismiss things out of hand? We’d still be in the stone age!

Michael Licona says

“Historians should approach the data neither presupposing nor a priori excluding the possibility of God acting in raising Jesus. They should instead form and weigh hypotheses for the best explanation. Probability ought to be determined in this manner rather than by forming a definition of a miracle that excludes the serious consideration of a hypothesis prior to the examination of the data

Mike Licona, The Resurrection of Jesus, p177

Some will look at the evidence for the resurrection, but still judge their final conclusion while including the prior probability and background knowledge of people rising from the dead and say the prior probability of a resurrection happening is so low.

It says they don’t happen regularly—that no amount of evidence can overcome that. This essentially suffers from the same circular conclusions we covered on prior slides. But if this was true, that the prior probability placed such a high role in determining how likely an event is, then we should conclude that any event in history that occured just once, never has enough evidence to back a warranted belief it happened.

Why?

If an event occurs only once, it has a low prior probability of it taking place. And therefore, every event that has happened once, probably did not happen, regardless of how much evidence we have for it Actually happening.

One famous example Bart would have issues with would be the event of Hannibal crossing the Alps with elephants. Such an event did not happen prior and it hasn’t happened since. We don’t know how Hannibal was able to do this, or even which path he took. It is actually quite miraculous that he was even able to do it without modern technology. But does the fact that no one ever completed it prior mean it did not happen with Hannibal? Of course not, and we have sufficient historical evidence that it did occur, which is even less evidence than Jesus’ resurrection has. Such with Hannibal, all we have is much later Roman sources.

The fact that an event only happened once doesn’t create a serious background knowledge problem for the actual evidence given for a single unique event. If the evidence is sufficient to account for it. In clear terms, background knowledge cannot be used automatically to say the evidence can never be adequate.

Troia Capta Polybius, The Histories Books 28-39

Also when it comes to background knowledge, if God did exist, who’s to say miracles can’t happen?

The background knowledge can be overcome and we can look to arguments for God’s existence to increase the possibility of God’s existence. If God possibly exists, then miracles as surely possible within an omnipotent, omniscient being

We also need to note Ehrmans claim is also self-defeating. He states that the resurrection is a theological claim, not a historical claim, so the historian cannot say whether the resurrection is probable or not because it is outside the scope of what the historian can say.

If this is the case, all he has done is refuted his own argument because now he cannot say the resurrection is improbable—Because that is making a claim about the probability of the resurrection.

Why is he claiming the resurrection is the least probable when by his own words that claim of probability cannot be made by a historian?

We can also ask, why Ehrman presupposes historians cannot evaluate miracle claims? Where is this rule set in stone? That historians are excluded from evaluating certain claims in history just because it might infer the existence of something beyond the natural? Ehrman makes this claim often, but never backs this fact up, and there’s good reason. Not all historians agree with Ehrman on this;

Historian trained John Hopkins and Princeton university professor David Hackett Fischer says

“specific canons of historical proof are neither widely observed nor generally agreed upon.”

Historian Yale-trained professor, Thomas Haskell says

“History, unlike English and Philosophy, lacks even the possibility of defining a single canon familiar to all practitioners”

Many historians, secular and Christian, feel evaluations of miracle claims is perfectly acceptable, like the following: Tucker; Wright; Ludemann; R.Brown; O’Collins; Habermas; Craig.

Whereas others disagree such as: Mccullagh; Ehrman; Meier; Dunn; Wedderburn; Theissen; Carnley.

So why is Ehrman just deciding Ad-hoc, the rules of history exclude the evaluation of miracles when that has not been agreed upon? Or proven to be the case? There is no a priori reason historians have to exclude the study of miracles.

Historians’ Fallacies, p62 Objectivity is not Neutrality: Rhetoric vs. Practice in Peter Novick’s That Noble Dream p153. See a complete list in Licona’s Resurrection of Jesus, p181.

Finally, Ehrman likes to try one more trick.

If we are willing to say Jesus rose from the dead based on the evidence we have, we also have to conclude other miracles of other religions have happened as well based on the same testimony of witnesses. This is an attempt at an Reductio ad absurdum. By saying if the resurrection is true, then other miracle claims have to be also true. However this idea fails for several reasons

See Ehrmans Argument, p242, The New Testament

Reductio ad absurdum definition: It is an Appeal to extremes. A form of argument that attempts either to disprove a statement by showing it inevitably leads to a ridiculous, absurd, or impractical conclusion, or to prove one by showing that if it were not true, the result would be absurd or impossible.

Firstly, Christians are not outright going to reject reports of other miracles, even from other religions.

It’s key to remember we believe there are other powers at work, some good and some evil.

So other miraculous events happen, they will cohere just fine with our worldview. It is not going to create the turmoil Ehrman and other atheists who use this argument think it will. All that will do is confirm our belief there are spiritual powers at work.

Second, even though there are good reasons for holding to the historicity of Jesus’ resurrection, that doesn’t somehow transfer credibility to other supposed miracle workers in other religions. Miracle claims are judged by a case-by-case basis based on what evidence each claim has specific to it. Just because we grant one miracle happened, that doesn’t open the floodgates. In the same way, just because some people from the middle-east are Muslims, that doesn’t mean they all are.

Third, many of these other miracle claims do not have nearly the amount of evidence the resurrection has. As Anthony Flew, a once notorious atheist even admitted “The evidence for the resurrection is better than, for claimed miracles in any other religion. It’s outstandingly different in quality and quantity…”

And many of these supposed miracles have been addressed. Tim Mcgrew addressed several miracles Hume tried to bring up and Mike Licona knocks down several of Ehrman’s biggest examples in his works. So many of these additional miracles can be found to be lacking in evidence and even have contrary evidence to counteract them.

Fourth and most importantly, any sceptic who tries to refute the resurrection with a reductio ad absurdum, only ends up shooting themselves in the foot, because they are essentially arguing miracles can and have happened and thus defeating naturalism for us.

So no naturalism, they’re not an atheist, they agree other miracles have happened, why are we still arguing? They’ve admitted miracles and they can’t if they want to hold genuinely this position.

It does nothing to make naturalistic theories look like the best explanation of the facts.

It doesn’t address the resurrection at all. So let critics bring up other miracles.

So

- They disprove naturalism

- Further add to God’s existence and that of miracles

- We can review miracles case by case

- We live in a spiritual world that further aligns with the Christian worldview

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reductio_ad_absurdum Anthony Flew, Did the resurrection happen p85. Blackwell companion to natural theology, p637-659 The Resurrection of Jesus, p171-182 https://simmonsopinions.com/2018/04/03/miracles-or-a-series-of-unfortunate-events/comment-page-1/

Ehrman’s argument is nothing more than a semantic twist on the same argument Hume employed.

It is circular and It does nothing to address the evidence for the resurrection.

He should do what other sceptical historians do which is offer a more rigorous theory to which he thinks best explains the evidence (like these scholars attempted: Geza Vermes’ in his ‘The Resurrection and Gerd Ludemann ‘The Resurrection of Christ, a Historical enquiry)’.

But as we have seen, no theory can explain the evidence with the explanatory scope and power of the resurrection theory. Unless one argues from a biased position and clings to a naturalist or non-christian worldview, there is no reason to dismiss the resurrection outright, it best explains the data and no other theory comes close.

R. F. Holland argues that miracles are: “a remarkable and beneficial coincidence that is interpreted in a religious fashion.” Holland sees miracles not as violations of Laws of nature, but rather as coincidences.

He takes on board a lot of what Hume argues and agrees that if there were several reasonable witnesses then the Law of nature would have to be revised or falsified as non-existent (Define miracles out of existence is his approach). However he agrees that this would not be a simple thing to do so it is better to see miracles as coincidences. He quotes a famous example where a child is stuck on a railway line in a pedal car. A train is coming, but the driver fails to see the child. However just in the nick of time the driver faints, his hand is taken off the lever and the brake is automatically activated. The train then stops in front of the child. There is no violation of nature, however for a religious person this may have religious significance and be thought of as a miracle. This is more a case of seeing an event as a miracle. There is no hand of God; rather the onus is clearly on the interpretation of person.

Tillich seems to follow a similar narrative problem. This is an interesting concept of miracle as it has little to do with violations of laws of nature, but more to do with the impression it makes on the person, Whether it leads them to change the direction of their life and whether it has any religious significance. So it focuses more on the consequences and effects it has on the person. What this means is that natural events may be perceived as a miracle and have religious significance for the person witnessing the events. For example, a person has been brought back to life that has been dead for three days. Even if it could be proved that the person had only been comatose, this might still be seen as a miracle by the observer owing to the impression it makes on him or her. He argues that a miracle is an event that does not contradict the rational structure of reality. An agnostic/atheist philosopher such as Michael Ruse might take a view similar to this, during his debates he often state the “feeling in the heart” as more important than a physical resurrection.

But all this is is another attempt to define genuine miracles out of existence and avoid the evidence question. What Holland and Tillich describe are perhaps reactions to either genuine natural miracles as described by Aquinas, they don’t address supernatural, they come from a perspective that it’s not worth talking about something that doesn’t exist, when we know there are degrees of evidence which can be presented. And Paul makes quite clear in 1 Corinthians 15:15 (A Chapter devoted to a physical resurrection) that if Jesus did not physically (anastasis in the ancient greek meaning bodily rising) rise from the dead, then our preaching is worthless and we should be pitied. Paul is clear, if he only was a feeling in our heart and not a physical resurrection, then the Christian faith is worthless.

The Christian faith is built around a physical resurrection, embedded as an event in history with evidence of written and spiritual testimony that to this day makes a strong case for Christianity, standing up to these ‘extraordinary claims’ required.

Inspirational source